Introduction

Manhattan, long regarded as a bastion of East Coast Liberalism and “New York values,” is reinventing itself. Since Superstorm Sandy in 2012, climate change has become prominent in a city already lightly engaged with environmental issues. In September of 2014, the largest climate march in history filled the streets of New York with the city’s mayor at the front of the throng. Avaaz.org, a campaign group involved in organizing the event, advertised it on the subway with the slogan: “What puts bankers and hipsters in the same march?”

As anyone who experienced the destructive impact of Sandy knows, there was no uniform effect of the devastating hurricane. Rather than being a great leveler, this superstorm—turbo-charged by the changing climate—ripped the city open and displayed its inequalities to the world. For many, the storm was characterized by the iconic image of the Goldman Sachs building, lit up with blazing lights but surrounded by a pitch black lower Manhattan.

On the east side of the island, not so far away, elderly New York Housing Authority (NYCHA) residents were trapped in their homes without food or medication as the elevators in their building failed to function without electricity. Another chapter in what Mayor Bill de Blasio called “a tale of two cities,” the "green" initiatives of post-Sandy New York demonstrate the substantial inequalities prevalent in New York's imagining of itself as a 21st century metropolis – one staggeringly rich and resilient, the other marginalized and critically exposed.

We conceived this project to get to know the many geographic areas contained in the landscape of a climate-changed Manhattan. More than just the impacts of unpredictable weather, flooding, and blackouts, we wanted to know: what’s the story with “green” initiatives within different areas of Manhattan that are put forward as part of the solution to the climate crisis? Is the new wave of green urban development widely available to people from all kinds of backgrounds? Or is it a boutique premium consumer product for the wealthy, like a half liter of organic aloe water from Wholefoods? Who benefits, and who is left in the figurative and literal shade?

The maps and essays we’ve included here cover several issues. The first section, “Whose Responsibility?” covers one aspect of energy, without which we can’t possibly understand the environmental landscape of the city. Manhattan, the densely built epicenter that never sleeps, uses a great deal of energy in its high rise buildings, whether they’re office or residential blocks. When we talk about “climate change,” it’s helpful to think about whose lights we’re keeping on when we burn all that coal and gas.

The second section, “Whose Impacts?” looks at what climate change might mean to different Manhattanites.

The third section, “Whose Green?” takes us back to energy: where the old, fossil fuel infrastructure is found, and where the new solar developments are cropping up. This information is crucial to understanding what the shift to renewables looks like when it comes to markers like race and class. Who has the capital to invest in solar panels on their apartment rooftops? And who will still be stuck living next to gas-fired power stations and refineries, or with diesel-oil heating in their building? It’s also where we look at luxury buildings: the ones that market themselves as “green,” as well as the ones that tower over the city, blocking light for neighbours, flora and fauna alike.

Finally, the forth and last section, “Doing It Better?” highlights a modest hope story of what a more just Manhattan could look like in a climate-changed world.

With each map, we hope to illustrate the environmental, economic, and social stakes discussed in our selected text, and to consider more thoroughly questions such as what kind of green Manhattan we are building, and for whom are we building it?

1. Whose Responsibility?

From “Climate Works for All: A Platform for Reducing Emissions, Protecting Our Communities, and Creating Good Jobs” by the Blue Green Alliance

Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, New York City adopted a concerted strategy to address emissions from these large buildings with mixed results. The City’s Greener, Greater Buildings Plan (GGBP) established a series of laws in 2009 to address building emissions. Despite the breadth of these laws, they fail to require energy efficiency retrofits in large privately-owned buildings.

Large buildings in New York City, defined as 50,000 square feet and above, make up only 2 percent of the City’s building stock, but use 45 percent of citywide energy.

2. Whose Impacts?

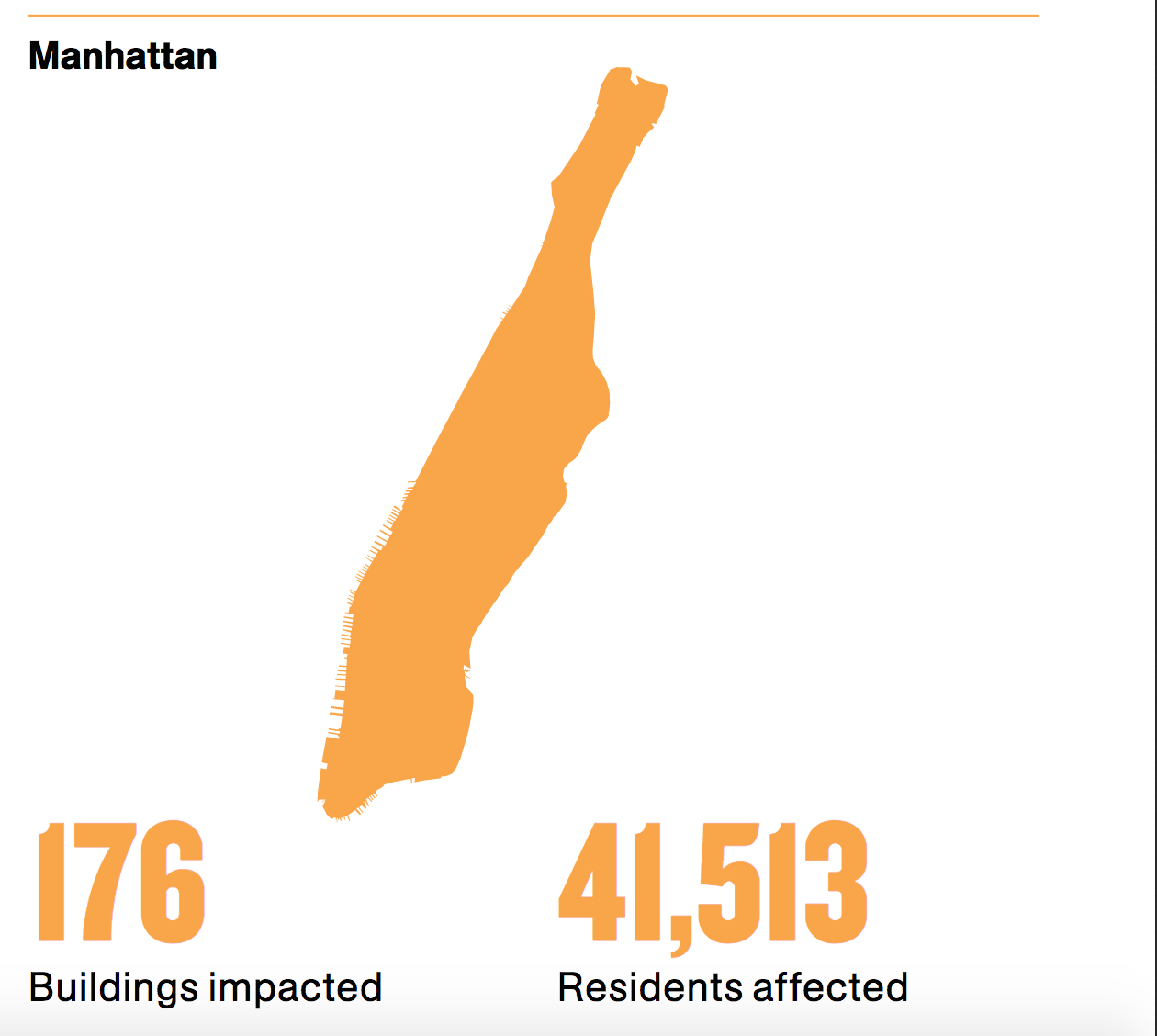

From “Weathering the Storm: Rebuilding a More Resilient New York City Housing Authority Post-Sandy” by the Alliance for a Just Rebuilding

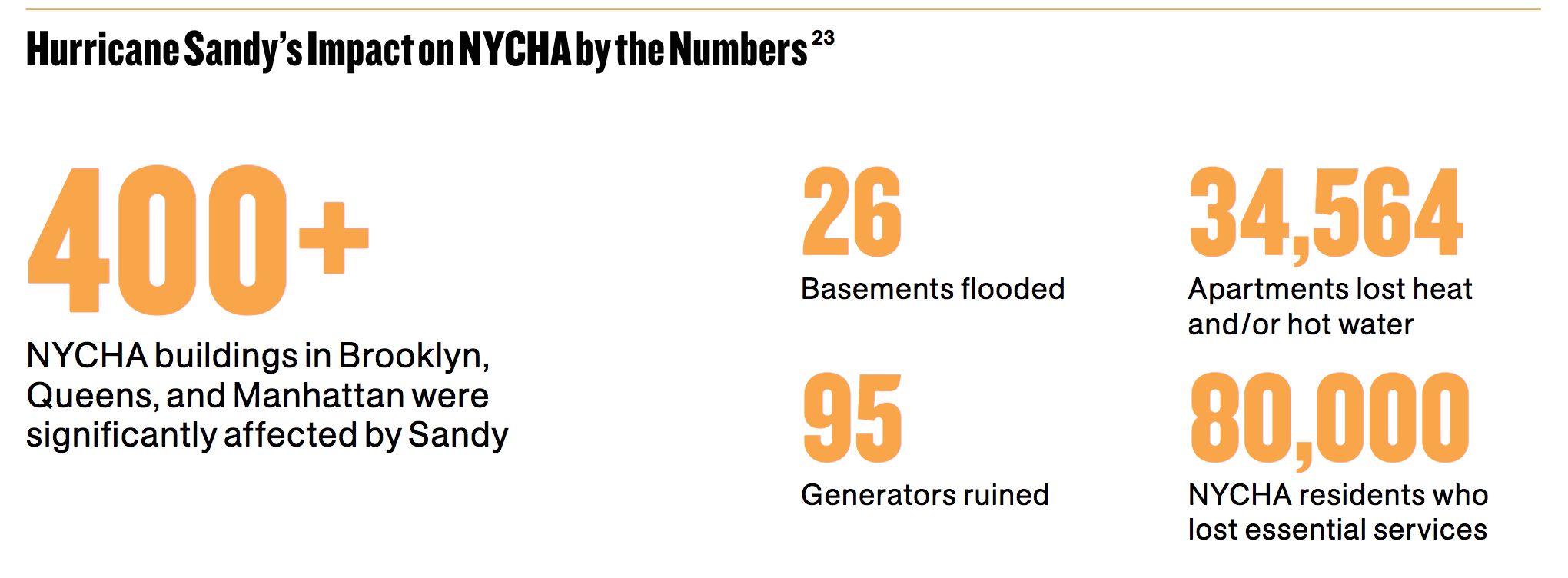

When Hurricane Sandy hit New York City on October 29th, 2012, approximately 80,000 people residing in over 400 NYCHA buildings lost many essential services such as electricity, use of elevators, heat and hot water. The City’s response to Hurricane Sandy was slow and communication to residents before, during, and after the storm was inadequate.

As a result, many community-based organizations stepped in to provide relief to residents in need. More than a year after Sandy, residents in hard-hit areas across New York City still face serious problems related to the storm such as mold, elevator malfunction and rodent infestation. These problems were uncovered and exacerbated by Sandy but they are not new; policy choices and disinvestment over the last decade have caused NYCHA residents to live in an ongoing state of neglect.

In addition to serious flooding, Sandy also left most residents on the Lower East Side without power for at least a week, with some not having their power restored for nearly a month. Many residents, particularly the elderly and those with limited English proficiency, were unable to get information and access critical services in the immediate aftermath and even long after the storm. Without electricity, elevators were not working, trapping seniors and residents with disabilities in their apartments. Many of these buildings also rely on electric pumps to bring water, and the lack of electricity left these buildings without running water.

The flooding also damaged underground phone lines, leaving people without phone service well after the storm. Despite all of these issues, the response of government, including the Mayor's Office, the Office of Emergency Management (OEM), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and NYCHA, did not fully address the needs of LES residents following Sandy. While community groups and local elected officials and their staff provided on-the-ground relief, coordination, and filled the holes of the government effort, residents still struggled in the days and weeks after the storm.

Climate change will have severe and long-term effects on New York City residents. In the short-term, New Yorkers will see increased flooding and storm surges. The most severe long-term climate impact for New Yorkers will be rising sea levels. By the end of the century, sea level is likely to rise up to four feet, with a 1 in 100 chance that it will rise seven feet. Given New York City’s 520 miles of coastline and dense residential development on the waterfront, as well as significant commercial, industrial and energy infrastructure located at or near sea level, the danger of rising sea levels to people and the economy is clear. The intensity and reach of storm surges, like during Superstorm Sandy, will be expanded by these higher sea levels. In fact, the impact of Superstorm Sandy was exacerbated by higher sea levels that had already occurred over the last century. Heat waves are very likely to become more frequent, increasing the risk of heat-related death.

By the end of the century, sea level is likely to rise up to four feet, with a 1 in 100 chance that it will rise seven feet.

By late century, we could experience nearly 60 days per year with temperatures over 90 degrees, whereas today we have about 18 such days per year. This has direct implications for those vulnerable to heat, such as the elderly, young children, workers whose jobs are outside, low-income people who can’t afford air conditioning, and those living in substandard housing. Extreme heat therefore has health and productivity implications for New York City residents. In addition, the spike in extremely hot days will increase the energy needs in the city to power air conditioning units. This will force New York City to invest in new and expanded energy sources and more resilient distribution networks at a high cost to taxpayers.

Although most New Yorkers will suffer from some aspects of climate change, poor and low-income residents will be hardest hit. Low-income communities sit at a nexus of physical, political, and financial forces that leaves them most vulnerable to extreme weather events and other impacts of climate change. Nearly half of New Yorkers live at or near the poverty line. Fifty-five percent of Superstorm Sandy’s storm surge victims in New York City were renters, with incomes averaging $18,000 a year. Sixty-four percent of homeowners impacted by Sandy earned less than $28,000 a year. Nearly 20,000 undocumented immigrants lived in Sandy affected areas, yet they are excluded from most sources of relief.

Fifty-five percent of Superstorm Sandy’s storm surge victims in NYC were renters, with incomes averaging $18,000 a year.

The storm revealed deep fault lines caused by economic inequality in our city; low-income communities and residents were disproportionately affected by Superstorm Sandy:

- Forty-one percent of New York City housing units impacted were designated as low-income, subsidized, rent-stabilized or Mitchell-Lama housing.

- Fifty-five percent of the storm surge victims in New York were very low-income renters, whose incomes are $18,000 a year on average.

- Nearly 20,000 undocumented immigrants lived in Sandy-affected areas, yet they are still excluded from most sources of relief.

- Over 400 New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) buildings—housing about 80,000 residents—lost essential services, such as electricity, heat, hot water and use of elevators. Despite evacuation orders, most residents sheltered in place due to poor health, lack of mobility, fear, unclear evacuation plans, and lapses in communication from NYCHA.

- Over 622,000 New Yorkers live in storm surge zones that are within a half-mile of the City’s six Significant Maritime & Industrial Areas—430,000 of these residents are people of color.

The low-income and unemployed New Yorkers living in areas of the city that were hit hard by Superstorm Sandy suffered disproportionately and were least able to recover due to a lack of financial resources. In fact, the Sandy Regional Assembly Recovery Agenda, prepared by nearly 200 participants from across the region in Sandy’s wake, identified over $500,000 in climate adaptation capital projects and dozens of policy recommendations to increase the resiliency of frontline communities. While some of these recommendations were included in the Mayor’s Special Initiative for Rebuilding and Resiliency Report and the Federal Hurricane Sandy Rebuilding Task Force Strategy, many were not. Any future plan to address climate change in New York City must prioritize these climate-vulnerable communities.

From "North Manhattan Climate Action Plan" by WeACT

The North Manhattan Climate Action’s study area encompasses the neighborhoods of Inwood, Washington Heights, West Harlem, Central Harlem, and East Harlem (Figure 1). Over 600,000 people, mostly African American and Latino, reside in these neighborhoods. Over 20% of the area’s residents live in poverty, a rate substantially greater than the rest of Manhattan’s 14% average.

Inequality across NYC is severe and growing. 20% of all household earners control over 54% of the City’s wealth. Since 1990, the median income of the top 1% of earners grew from $452,415 to $716,625, while the bottom 10% of earners saw their income increase only modestly, from $8,468 to $9,455. This gaping wealth disparity also translates into an advantage in political power and access to resources for the wealthy. For this reason, some NYC residents are dramatically better prepared to absorb the shocks associated with climate change than others.

In terms of the physical impact that climate change will have on Northern Manhattan, it is predicted that by the year 2100 we could see temperatures climb by up to 8°F, sea levels rise by up to six feet, precipitation increase by 13%, and what are now once-in-100 year floods occur once every eight years. These are “worst-case scenarios,” but even the best-case scenarios represent a grave threat to Northern Manhattan’s people and infrastructure, including utilities and transportation routes critical to function of the entire city. As we invest billions in preparations for climate change, we must leverage our efforts to address other social crises, such as chronic unemployment, poor diets, mass incarceration, and low-quality education, among others. Otherwise, we may prevent climate change from erasing NYC only to watch the slower erosion of gentrification swallow what’s left of it.

From “Housing Agency’s Flaws Revealed by Storm” in The New York Times

A 2009 report by the city drafted in response to Hurricane Katrina recommended that the authority elevate certain critical pieces of equipment stored in its basements, renovations that were never done. City officials noted that the floodwaters from Hurricane Sandy reached so high that even the elevated equipment would have been damaged. The agency also did not set up “standby contracts” that would allow the city to quickly secure pumps, generators or other supplies and equipment in an emergency. Such contracts are common in federal disaster planning protocols, although they often come at a price as companies charge a fee to reserve generators or other gear.

But the need for such equipment became painfully apparent the day after Hurricane Sandy hit. Around the city, 26 of the housing authority’s basement boiler rooms had flooded, destroying the equipment there, and leaving 34,565 apartments without heat and hot water. The electrical systems of many buildings, already in marginal shape because of delayed maintenance, were also devastated by flooding. Having power restored would not be enough: in about 95 buildings, temporary generators and boilers would be needed until the electrical systems could be rebuilt.

Around the city, 26 of the housing authority’s basement boiler rooms had flooded, destroying the equipment there, and leaving 34,565 apartments without heat and hot water.

Water stopped flowing in many high-rise buildings above the sixth floor. Stairwells and hallways were pitch black. But because there was no up-to-date survey of electrical needs, the Army Corps of Engineers, called in to help install generators five days after the storm, first had to visit 100 authority buildings simply to determine what kind of generator each needed. As much of a struggle as it was to restore services, the City’s effort to get food and medical help to those trapped—and even grasp just how many people were in peril—was even more fraught.

It began with good intentions: three days after the storm, on November 1, the City enlisted a half-dozen nonprofit groups to conduct a formal canvass of high-rise buildings in the flood zone. The City had solid evidence that the needs in these towers were most likely great: only 6,800 people had shown up at shelters citywide, even though 375,000 lived in the mandatory evacuation zone, including 45,000 from public housing.

But the City had no standing agreement with the groups to conduct such a door-to-door effort, or explicit protocols for how it should take place, and many of the teams were sent out without escort by the National Guard, which meant they were unable to gain access to many buildings, said Linda I. Gibbs, another deputy mayor. “It was not as strong as we thought it needed to be,” she said of this initial effort. “We needed to stand up a more deliberate effort, so we could get access.”

On November 5, as the subway system returned to service and schools in New York City reopened, Mr. Bloomberg was feeling confident that the Housing Authority had a handle on the situation in its buildings. “We may be able to surprise everybody over the next two, three, four days and get everybody, or almost everybody, back,” Mr. Bloomberg said at City Hall.

It was not until November 9—11 days after Hurricane Sandy hit—that Mayor Bloomberg announced a much more robust effort to reach out to tenants of buildings still without power and heat.

Volunteer groups like People’s Relief in Coney Island and Occupy Sandy set up curbside medical clinics and rallied teams of people to go door to door searching for trapped residents. They appeared to be better organized than the city. In Red Hook, the logs created by volunteers reflected the evolving needs of tenants: batteries gave way to ice for chilling medicine and adult diapers. “DEAF: Knock Hard,” said the entry next to one man’s name.

Some volunteers felt the roles should have been reversed, with the city leading them. But Nazli Parvizi, the city’s commissioner for community affairs and the mayor’s point person in Brooklyn, said she felt effective in a supporting role. The volunteers were doing a good job, she said, and “I wasn’t here to change that narrative. I was asking them, ‘What do you need?’”

It was not until November 9—11 days after Hurricane Sandy hit—that Mayor Bloomberg announced a much more robust effort to reach out to tenants of buildings still without power and heat. This time health care professionals hired by the city under an emergency contract would all be accompanied by the National Guard, and the housing authority and other landlords were informed in advance, to make sure they could get access to all the buildings. The city also asked the federal government to set up “pop-up” hospitals at certain sites.

From “Goldman Sachs Was Not Washed Away in Hurricane Sandy” in New York Magazine

Amid the frenetic news coverage of Hurricane Sandy, a photo of Goldman Sachs's 200 West Street headquarters (above) made the rounds. The photo, which appeared to show Goldman's building lit by a backup generator while many buildings in Lower Manhattan were darkened by power outages, drew anger on Twitter.

The fact that the NYU hospital is dark but Goldman Sachs is well-lit is everything that's wrong with this country.

— Ken Shadford (@kenshadford) October 30, 2012

But Goldman spokesman David Wells told Daily Intel on Tuesday that Goldman's building had been only one of many in the neighborhood to stay lit. (Indeed, in the photo, the building on the right, across the street from 200 West Street, appears to have power as well.)

"We weren’t the only building with light, but we do have a generator," Wells said. "We’re not drawing power from the grid." Wells said that emergency storm preparations, including a massive wall of sandbags outside the front entrance to 200 West, had helped both the bank's Manhattan and Jersey City locations avoid major damage. Goldman employees are working from home today, and officials are hoping to open the Manhattan office for at least limited use on Wednesday.

Policy choices and disinvestment over the last decade have caused NYCHA residents to live in an ongoing state of neglect.

Meanwhile, Citigroup said that its investment bank headquarters, also located in Zone A, sustained "minor flooding" during the storm and was still without power, according to Reuters. Both the New York Stock Exchange and the Nasdaq will open for trading tomorrow, with the NYSE reportedly planning to use a backup generator for power.

Update: Goldman Sachs president Gary Cohn just appeared on Bloomberg TV, where he confirmed that the bank's buildings had only been slightly damaged by the storm, and said that Goldman was assembling a task force to help non-employees in Battery Park City who were hit by the storm. "We completely feel an obligation to the neighborhood," Cohn said.

3. Whose Green?

From “After the People’s Climate March, It Is Time to Demand More” in Common Dreams

The 400,000 people who packed Manhattan’s Central Park West for the People’s Climate March on September 21 have all gone home to their apartments, farms, cabins and lobster boats. They’ve returned to Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and the Wet’suwet’en territory in British Columbia, to the Philippines and the Pacific Islands. The “U.N. Climate Summit” banner that, last week, formed the backdrop for the impassioned speeches of 120 heads of state along with Leonardo DiCaprio, has been taken down. Debate in the newly renovated General Assembly Hall has turned to terrorism, a different kind of security threat than that posed by drought and rising sea levels. The metal barricades erected against protesters who flooded the heart of global capitalism at last Monday’s Flood Wall Street demonstration have been cautiously removed by the New York Police Department. Frostpaw the polar bear has gone to jail.

The New York City subway advertisements purchased by Avaaz, a multi-million dollar nonprofit that describes itself as a “global civic organization,” were telling. One ad solicited people to “Walk dog, eat brunch, and make history,” while another asked, “What puts bankers and hipsters in the same march?”

Far from recruiting the working, poor and diverse communities of color that compose the bulk of the Metropolitan Transit Authority’s riders to join the march, the slogans appeared to trivialize the mobilization and to be geared towards recruiting a wealthy, privileged base.

It is important to note that, aside from a small “Carbon-Free Capitalism” contingent organized by green investment firms, very few bankers actually participated in the march, nor did Avaaz take corporate money, as many believed the ads indicated. Avaaz is entirely crowd-funded and does not accept donations of more than $5,000. The ads were indicative, however, of the dominant liberal ideology that characterized the march organizing and indeed pervades the U.S. political climate as a whole. It may sound incredible, but despite environmental justice groups, primarily those in the Climate Justice Alliance, playing a large part in the organizing process, class and racial analysis were largely avoided within the broader organizing drive. The general effect was one of de-politicization in favor of creating a big tent.

From “Race, Class, and Disaster Gentrification” in Tidal Magazine

In the days and weeks following Hurricane Sandy the inequalities at the heart of New York City could scarcely be missed. While hundreds of thousands of public housing residents went without heat, hot water or electricity, Mayor Michael Bloomberg rushed to get the stock exchange up and running within 48 hours—a stark reminder of whose lives and well-being are valued by current administration. In the immediate aftermath of disasters such contrasts lay bare the violence of race and class. Who is able to leave and who is able to return are questions about access to resources, vulnerability, and the existing geographies of economic and social inequality. But it is through the process of reconstruction that existing racial and class iniquities are truly reproduced and deepened. In New York City, as the power has finally come back on for residents and as reconstruction efforts plod along, it is perhaps time for a look at how these dynamics are playing out.

From "The Northern Manhattan Climate Action Plan" by WE ACT

As Melissa Checker points out in her article “Wiped Out by the “‘Greenwave’,” our overdependence on systems of private investment leads to “environmental gentrification,” which appropriates the “successes of the urban environmental justice movement…to serve highend redevelopment that displaces low income residents.” In other words, “the efforts of environmental justice activists to improve their neighborhoods...now help those neighborhoods attract an influx of affluent residents.”

As stateed in the promotional materials for Avalon Clinton, a luxury apartment complex:

As an environmentally friendly building in Manhattan’s Clinton neighborhood, Avalon Clinton offers 23,000 square feet of LEED- certified apartments for rent. With roof gardens, two fitness centers, and a private garage, the well-furnished apartments at Avalon Clinton combine sustainability and luxury flawlessly.

From "Supersizing Manhattan: New Yorkers Rage Against the Dying of the Light” via The Guardian

The buildings are making the city less pleasant for anyone who cannot afford one of the condos in the sky. Think of it as the new Upstairs, Downstairs, but on an urban scale.

From "Developers are Turning Central Park into Central Dark with Mega-Thin Towers" via New York Daily News

Welcome to Central Dark.

A new generation of mega-tall skyscrapers being built along 57th St. for foreign billionaires will cast a long shadow over New York’s premier greenspace, a new report shows.

"It’s troubling that the sky's the limit when it comes to one of our most precious public spaces," said Vin Cipolla, president of the Municipal Art Society, which conducted the report to highlight the need for oversight of development around parks. "We need to protect these spaces," Cipolla added.

The shadow report reveals the worst-case scenario — every Dec. 21, the winter solstice, the sunless zone will extend 20 blocks into Central Park and reach the Lake and Ramble. Every Sept. 21 at 4 p.m., shadows would stretch a dozen blocks — as far as Sheep Meadow and the Naumburg Band Shell near the 72nd St. transverse.

The skyscrapers in question are rising “as of right,” meaning the public has no say over their size. Developers are able to build so high because they bought air rights from neighboring buildings — and technological advances now allow for the construction of super thin mega-towers on small footprints traditionally suited for 40 story buildings.

One of the studied towers, the Gary Barnett-designed One57 across from Carnegie Hall, reaches 1,004 feet. Just down the block is the proposed 1,350-foot minaret at 111 West 57th St., next door to the Steinway Building. It’s only 43 feet wide — the width of two townhouses — and it’s higher than the Empire State Building’s observation deck.

Nearby, Harry Macklowe is building the 1,397-foot 432 Park, taller than the World Trade Center minus its spire, and Barnett is working on a follow-up at 57th St. and Broadway that could reach 1,500-feet, making it the tallest apartment building in the Western Hemisphere.

The Municipal Art Society proposes that any project with significant shadow impacts on major public spaces should undergo public review. This would give public officials and the community board the opportunity to weigh in. "We should be studying these impacts before the buildings are going up, not after, when it's already too late," said Cipolla.

Skyscraper boosters disagree. “I don't think it's right to change the rules overnight," said Carol Willis, director of the Skyscraper Museum.

This is not the first time the Municipal Art Society has taken up the cause of shadows over Central Park. In the 1980s, the group led a campaign with former first lady Jackie Onassis to stop a pair of towers on Columbus Circle. The buildings were eventually build — but the resulting Time Warner Center was hundreds of feet shorter and set back from the park.

From “Meet the House that Inequality Built: 432 Park Avenue” via Fortune Magazine

Along a stretch of New York City’s Park Avenue, between 56th and 57th Street, soars a tower so jaw-droppingly altitudinous that King Kong himself would likely think twice before scaling it. Its rooftop, roughly a quarter of a mile high, makes it the tallest building in New York and the highest residential tower in the western hemisphere.

At 96 stories (1,396 feet), it has no company in the space it occupies atop Manhattan’s skyline. The Empire State Building tops out some 150 feet below that. Absent its spire, the newly built World Financial Center—itself a giant—is 28 feet shorter than this new cathedral to uber-wealth. 432 Park Avenue can be seen from all five boroughs of New York City, from inbound Metro-North trains coming in along the Harlem River, from the Meadowlands in New Jersey, and from several vantage points on Long Island. Its lone silhouette dominates the skyline from every angle. It demands your attention in a way that no residential building ever has.

The most remarkable thing about 432 Park, however, is not just its sheer size. It is the fact that, in a building so tall and imposing, with over 400,000 square feet of usable interior space, there are only 104 units for people to live in. 432 Park Avenue is, in short, a monument to the epic rise of the global super-wealthy. It is the house that historic inequality built.

Our story begins in 2009 with a little-known Los Angeles-based private equity firm called CIM. The firm’s three managing partners, a former Drexel Burnham banker and a pair of former Israeli paratroopers, quietly dropped in on Manhattan’s punch drunk post-financial crisis real estate market with money to spend. CIM moved quickly, writing checks to bail out some of the city’s most prestigious real estate families and firms, as projects were stalling and financing had all but dried up. The outsiders became Manhattan power players overnight.

Strong relationships with investment organizations like Blackstone and Calpers put the west coast-based firm in a position to capitalize on a once-in-a-generation opportunity in a city where the incumbents were largely overleveraged from the prior boom. They acted as the bank behind the resurrection of several high-profile distressed properties, and allowed the original developers to stay involved with each deal as their partners.

By 2011, CIM was everywhere. The economy was slowly improving, the financial firmament was beginning to thaw, and institutional investors were cutting checks again. It is in this recovering environment that a project as ambitious as 432 Park Avenue can even be dreamed of, let alone funded.

Harry Macklowe is one of the real estate industry’s most famous and colorful characters, with a massive portfolio of properties and projects to go along with his outsize personality. No stranger to gambles and calculated risks, Macklowe found himself in a bit of a squeeze in 2008, as the seams of the property market began to tear and the bills from New York’s decade of excess came due. A highly leveraged real estate transaction backed by a $5.8 billion loan from Deutsche Bank kept his name in the news, and his stake in several trophy properties, like the General Motors Building, were said to have been in jeopardy.

CIM stepped into the breach, providing financing for several of Macklowe’s troubled projects, and a partnership was born that would lead to the groundbreaking at 432 Park. By August 2011, their incredible plans for the tower—which would occupy the land where the Macklowe-owned Drake Hotel had been demolished—began to leak onto real estate news sites like Curbed and The New York Observer. The idea of a “fifth-act” survivor like Harry Macklowe partnering with a “mysterious” developer from out of town proved to be an irresistible storyline to the chattering classes.

Within a year, we began to get a sense of what 432 Park Avenue would come to represent. First, we learned that the number of condo units built would be closer to 100 than the originally planned 140. Next came details about the building’s sales efforts. Notably, while Macklowe Properties had kept 432 Park Avenue’s units off of popular broker databases like StreetEasy and the Residential Listing Service (RLS), the firm was going full-throttle in its attempt to court the Russian oligarchy. A kind of traveling sales office was set up at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel on Moscow’s Tverskaya Street, where dozens of billionaires pass through the lobby each day.

"There are only two markets,ultraluxury and subsidized housing.”—Rafael Viñoly, architect of 432 Park Avenue

By May 2013, Macklowe had announced that the top-floor penthouse was already sold for an astonishing $95 million. Half of the building’s apartments were under contract, with projections of $3 billion in total sales. This February, Manhattan realtor Douglas Elliman was brought on as the exclusive co-sales agent to help move the rest of the units.

It is widely believed that the building will only be one-quarter occupied at all times, even though it will be completely sold out. Keep in mind that these are pied-a-terres that begin at $7 million each and include several full-floor parcels in the $75 million range. More than anything else, this speaks to the insatiable appetite of the world’s greatly expanded billionaire class. Middle Eastern oil magnates, Chinese billionaires, Russian oligarchs, and the Latin American aristocracy all have one thing in common: More money than they know what to do with and a desperation to get as much of it out of their home countries as possible. New York real estate works very well as both a facilitator of this as well as a store of value.

As of this writing, there are currently plans for eight more ultra-luxe towers in and around Manhattan, in various stages of development. The explosion of wealth among ultra high net worth (UNHW) individuals around the world has made all of this possible. According to a new study from UBS and Wealth-X, there are 211,275 people in the world who could be considered ultra high net worth, with assets totaling north of $30 million. The approximate amount of wealth controlled by this group is estimated at just under $30 trillion. And while the number of UHNW people grew by 6% since 2013, their assets grew by 7%.

But these figures obscure an even more important trend taking root among the UHNW rankings: People with over a billion dollars in assets (there are 2,325 of them) saw their wealth increase by 12% year over year, while those at the bottom of the group—the 91,000 people with assets between $30 million and $49 million—realized a comparatively smaller 7% bump in wealth. Those at the top of the top are seeing their fortunes grow twice as fast as those at the bottom of the top. And the number of UHNW individuals who fall in the $750 million to $1 billion category saw their ranks swell by 20% this year to over 1,200 people. The bottom line is that the richer you are, the faster you’re getting even richer.

This explains why a city like New York can build dozens of ultra-luxury residential towers and continue to sell out. In New York alone, it is estimated that there are 8,655 full-time residents who would be categorized as ultra-high net worth, the most of any city in the world. Wealth-X finds that the average UHNW individual owns 2.7 properties and that 8% of their wealth is invested in real estate. Logically speaking, as their wealth grows, so too does their capacity to own and invest in an increasing amount of high-end housing.

This coming spring, the few dozen occupants of 432 Park Avenue, North America’s third-tallest building, will begin to move in. They will furnish their palatial apartments against a global backdrop of deflationary fears, central banks in perpetual crisis mode, massive unemployment, and stubbornly stagnating wage growth for 99% of the world’s population. In previous generations, when towers of this scale were erected, they were monuments to working. 432 Park, unlike the Chrysler Building, the World Financial Center, and the Empire State Building, is a monument to owning.

In the Medieval era, towers were erected to separate royalty and feudal overlords from the rest of the population during times of plague and suffering. It was an effective barrier, both physical and symbolic. A 1,400-foot skyscraper, in America’s most populous city, in which fewer than 100 people will reside, is perhaps the perfect present-day parallel to such behavior. The ascendance of 432 Park Avenue to its now-dominant place in the skyline says more about the state of our world than a thousand Thomas Pikettys typing on a thousand keyboards ever could.

4. Doing It Better?

From “Climate Works for All: A Platform for Reducing Emissions, Protecting Our Communities, and Creating Good Jobs” by the Blue Green Alliance

With an ultimate goal of protecting NYC’s most vulnerable from climate-related impacts, the NMCA promotes environmental policies that also aim to address socioeconomic inequality. The NMCA recognizes that issues of class, race, gender, ethnicity, and age, not simply rising sea levels and temperatures, must be mitigated and ultimately overcome.

Public school buildings have relatively large footprints and expansive rooftops, which are suitable for solar. In addition to expanding and properly financing and staffng energy efficiency, recycling and composting programs, public schools should take advantage of their expansive and underutilized rooftops by installing solar panels.